To end the Eurozone crisis, bury the debt forever

The Eurozone’s debt crisis is getting worse despite appearances to the contrary. How can we end it? This column presents five major options for reducing crisis countries’ debt. Looking into the details, it seems the only option that is both realistic and effective is for countries to default by selling monetised debt to the ECB. Moral hazard aside, burying the debt seems to be the only way we can end the crisis.

The Eurozone’s debt crisis is getting worse despite appearances to the contrary.

Eurozone bond rate spreads have narrowed – leading some to think that the crisis is fading.1 Yet the narrowing is not due to an improvement in fundamentals. It happened after the ECB announced its Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme. Mario Draghi’s, “Whatever it takes”, did the trick; investors believe the ECB could and would counter rising spreads in the medium term.2

But this means that the information in the spreads is muddled:

- Spreads no longer show us what investors think about debt sustainability.

- They reflect a mix of debt-sustainability expectations and forecasts of ECB reactions.

This is yet another instance of Goodhart’s Law – a variable that becomes a policy target soon loses its reliability as an objective indicator (Goodhart 1975).

How to gauge the Eurozone debt crisis

This leaves us with a coarser measure – the evolution of public debts – as a ratio to GDP. Spreads were clearly better indicators before OMT. There are plenty of problems with debt-to-GDP ratios:

- Gross debts are gross, i.e. they ignore public assets.

- Gross debts ignore unfunded public liabilities such as pensions and healthcare.

In most countries the unfunded liabilities – which include the potential costs of bailing out banks when and if they fail – are vastly bigger than the public assets that can be disposed of.

- GDP is a static measure of the ability to pay; GDP growth also matters.3

Noting that Eurozone growth seems to have slipped into a go-slow phase, the GDP denominator is likely to grow slower than it did in the 1990s.

The three points taken together suggest that debt-to-GDP ratios of the 2010s paint a more optimistic picture of sustainability than the same levels in the 1990s.

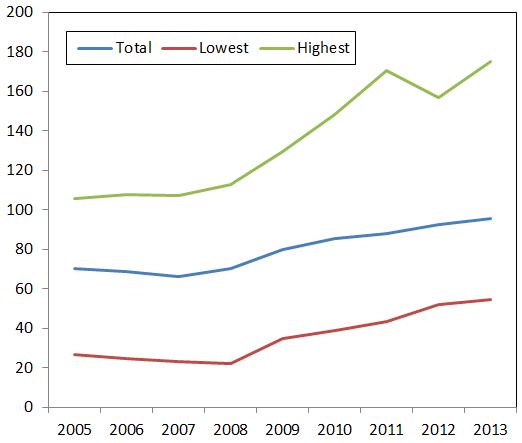

Be that as it may, Figure 1 displays the public debt to GDP ratio for the Eurozone as a whole, along with the highest and lowest member country ratios (ignoring the two special cases of Estonia and Luxembourg).

- Even including optimistic forecasts for 2013, the figure can only confirm that the situation is getting worse.

If public debt seemed likely to be unsustainable in 2008, the likelihood is even higher now. Strikingly, this holds even for Greece, in spite of the restructuring of its public debt in 2011, which was large enough to bankrupt the Cypriot banking system. Put differently, not only the initial problem has not been solved, it has also been made worse.

There can be no surprise here. Budget stabilisation cannot work during a recession as was pointed out at the outset of crisis (Giavazzi 2010, Wyplosz 2010).

Figure 1. Debt to GDP ratios in the Eurozone (%)

Source: AMECO-on-line, European Commission.

What are the options today?

The debt problem cannot be avoided or hoped away. When debt is unsustainable it will not be sustained. The only question is how and when the crisis comes. Here are the five options that can address the debt quagmire.